Sugar Gliders

The Sugar Glider (Petaurus breviceps) is a small, omnivorous, arboreal, and nocturnal gliding possum. The common name refers to its predilection for sugary foods such as sap and nectar and its ability to glide through the air, much like a flying squirrel. They have very similar habits and appearance to the flying squirrel, despite not being closely related—an example of convergent evolution. The scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, translates from Latin as "short-headed rope-dancer", a reference to their canopy acrobatics.

The sugar glider is characterised by its pair of gliding membranes, known as patagia, which extend from its forelegs to its hindlegs. Gliding serves as an efficient means of reaching food and evading predators. The animal is covered in soft, pale grey to light brown fur which is countershaded, being lighter in colour on its underside.

The sugar glider, as strictly defined in a recent analysis, is only native to a small portion of southeastern Australia, corresponding to southern Queensland and most of New South Wales east of the Great Dividing Range; the extended species group, including populations which may or may not belong to P. breviceps, occupies a larger range covering much of coastal eastern and northern Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands. Members of Petaurus are popular exotic pets; these pet animals are also frequently referred to as "sugar gliders", but recent research indicates, at least for American pets, that they are not P. breviceps but a closely related species, ultimately originating from a single source near Sorong in West Papua.[This would possibly make them members of the Krefft's glider (P. notatus), but the taxonomy of Papuan Petaurus populations is still poorly resolved.

Taxonomy and evolution

The genus Petaurus is believed to have originated in New Guinea during the mid Miocene epoch, approximately 18 to 24 million years ago. The modern Australian Petaurus, along with New Guinean members of what were formerly considered P. breviceps, diverged from their closest living New Guinean relatives ~9-12 mya. They probably dispersed from New Guinea to Australia between 4.8 and ~8.4 mya, with the oldest Petaurus fossils in Australia being dated to 4.46 million years. This may have been possible due to sea level lowering from about 7 to 10 mya, resulting in land bridges between New Guinea and Australia.

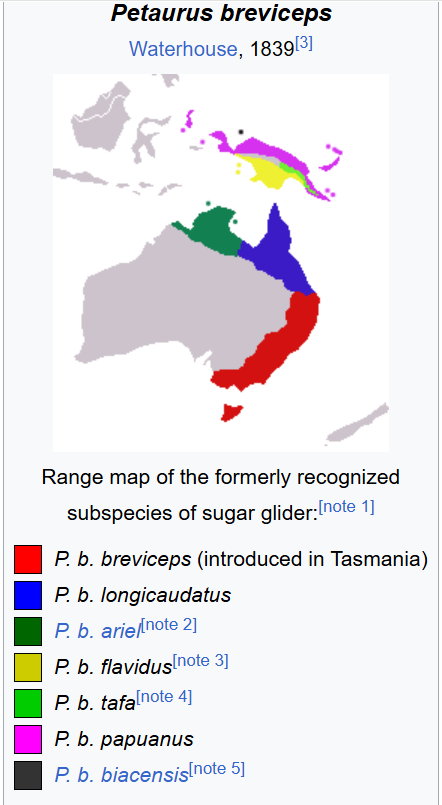

The taxonomy of the species is complex, and is still not fully resolved. It was formerly understood to have a wide range across Australia and New Guinea, being the only glider to have this distribution, and to be divided into seven subspecies, with three occurring in Australia and four in New Guinea. This traditional subspecific division was based on small morphological differences, such as colour and body size. However, a 2010 genetic analysis using mitochondrial DNA indicates that these morphologically defined subspecies may not represent genetically unique populations.

Lack of the white tip on the tail helps identify this as P. breviceps

Further studies have found significant genetic variation within populations traditionally classified in P. breviceps, sufficient to warrant splitting the species into multiple. The subspecies P. b. biacensis, from Biak Island off of New Guinea, was reclassified as a separate species, the Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis). In 2020, a landmark study suggested that P. breviceps actually comprised three cryptic species: the Krefft's glider (Petaurus notatus), found throughout most of eastern Australia and introduced to Tasmania, the savanna glider (Petaurus ariel), native to northern Australia, and a more narrowly defined P. breviceps, restricted to a small section of coastal forest in southern Queensland and most of New South Wales. In addition, other sugar glider populations throughout this range (such as those on New Guinea and the Cape York Peninsula) may represent undescribed species or be conspecific with previously described species. This indicates that contrary to previous findings of a large range (which in fact applied to P. notatus and, to a lesser extent, to P. ariel), P. breviceps is a range-restricted species that is sensitive to ecological disasters, such as the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, which significantly affected large portions of its habitat.

P. breviceps and P. notatus are estimated to have diverged ~1 million years ago, and may have originated from long term geographic isolation. The early-mid Pleistocene saw an uplifting of the Great Dividing Range, contributing to and coinciding with aridification of the interior of Australia, including on the western side of the range. This, as well as other climactic and geographic factors, may have isolated the ancestors of P. breviceps to refugia on the eastern, coastal side of the Great Dividing Range. This would be an example of allopatric speciation.

Distribution and habitat

Sugar gliders are distributed in the coastal forests of southeastern Queensland and most of New South Wales. Their distribution extends to altitudes of 2000m in the eastern ranges. In parts of its range, it may overlap with Krefft's glider (P. notatus).

The sugar glider occurs in sympatry with the squirrel glider and yellow-bellied glider; and their coexistence is permitted through niche partitioning where each species has different patterns of resource use.

Like all arboreal, nocturnal marsupials, sugar gliders are active at night, and they shelter during the day in tree hollows lined with leafy twigs.

The average home range of sugar gliders is 0.5 hectares (1.2 acres), and is largely related to the abundance of food sources; density ranges from two to six individuals per hectare (0.8–2.4 per acre).

Native owls (Ninox sp.) are their primary predators; others in their range include kookaburras, goannas, snakes, and quolls.[21] Feral cats (Felis catus) also represent a significant threat.

The sugar glider has a squirrel-like body with a long, partially (weakly) prehensile tail. The length from the nose to the tip of the tail is about 24–30 cm (9–12 in), and males and females weigh 140 and 115 grams (5 and 4 oz) respectively. Heart rate range is 200–300 beats per minute, and respiratory rate is 16–40 breaths per minute. The sugar glider is a sexually dimorphic species, with males typically larger than females. Sexual dimorphism has likely evolved due to increased mate competition arising through social group structure; and is more pronounced in regions of higher latitude, where mate competition is greater due to increased food availability.

The fur coat on the sugar glider is thick, soft, and is usually blue-grey; although some have been known to be yellow, tan or (rarely) albino.[a] A black stripe is seen from its nose to midway on its back. Its belly, throat, and chest are cream in colour. Males have four scent glands, located on the forehead, chest, and two paracloacal (associated with, but not part of the cloaca, which is the common opening for the intestinal, urinal and genital tracts) that are used for marking of group members and territory. Scent glands on the head and chest of males appear as bald spots. Females also have a paracloacal scent gland and a scent gland in the pouch, but do not have scent glands on the chest or forehead.

The sugar glider is nocturnal; its large eyes help it to see at night and its ears swivel to help locate prey in the dark. The eyes are set far apart, allowing more precise triangulation from launching to landing locations while gliding. Sugar gliders have demonstrated trichromacy in behavioral testing with sensitivity in the ultraviolet/blue, green, and red ranges. Ultraviolet sensitivity is corroborated by genetic evidence. The physiological source of their middle wavelength sensitivity is not yet confirmed.

Each foot on the sugar glider has five digits, with an opposable toe on each hind foot. These opposable toes are clawless, and bend such that they can touch all the other digits, like a human thumb, allowing it to firmly grasp branches. The second and third digits of the hind foot are partially syndactylous (fused together), forming a grooming comb. The fourth digit of the forefoot is sharp and elongated, aiding in extraction of insects under the bark of trees.

The gliding membrane extends from the outside of the fifth digit of each forefoot to the first digit of each hind foot. When the legs are stretched out, this membrane allows the sugar glider to glide a considerable distance. The membrane is supported by well developed tibiocarpalis, humerodorsalis and tibioabdominalis muscles, and its movement is controlled by these supporting muscles in conjunction with trunk, limb and tail movement.

Lifespan in the wild is up to 9 years; is typically up to 12 years in captivity, and the maximum reported lifespan is 17.8 years.

Gliding

The sugar glider is one of a number of volplane (gliding) possums in Australia. It glides with the fore- and hind-limbs extended at right angles to the body, with feet flexed upwards. The animal launches itself from a tree, spreading its limbs to expose the gliding membranes. This creates an aerofoil enabling it to glide 50 metres (55 yards) or more. For every 1.82 m (6 ft 0 in) travelled horizontally when gliding, it falls 1 m (3 ft 3 in). Steering is controlled by moving limbs and adjusting the tension of the gliding membrane; for example, to turn left, the left forearm is lowered below the right.

This form of arboreal locomotion is typically used to travel from tree to tree; the species rarely descends to the ground. Gliding provides three dimensional avoidance of arboreal predators, and minimal contact with ground dwelling predators; as well as possible benefits in decreasing time and energy consumption spent foraging for nutrient poor foods that are irregularly distributed. Young carried in the pouch of females are protected from landing forces by the septum that separates them within the pouch.

Torpor

Sugar gliders can tolerate ambient air temperatures of up to 40 °C (104 °F) through behavioural strategies such as licking their coat and exposing the wet area, as well as drinking small quantities of water. In cold weather, sugar gliders will huddle together to avoid heat loss, and will enter torpor to conserve energy. Huddling as an energy conserving mechanism is not as efficient as torpor. Before entering torpor, a sugar glider will reduce activity and body temperature normally in order to lower energy expenditure and avoid torpor. With energetic constraints, the sugar glider will enter into daily torpor for 2–23 hours while in rest phase. Torpor differs from hibernation in that torpor is usually a short-term daily cycle. Entering torpor saves energy for the animal by allowing its body temperature to fall to a minimum of 10.4 °C (50.7 °F) to 19.6 °C (67.3 °F).Whe n food is scarce, as in winter, heat production is lowered in order to reduce energy expenditure. With low energy and heat production, it is important for the sugar glider to peak its body mass by fat content in the autumn (May/June) in order to survive the following cold season. In the wild, sugar gliders enter into daily torpor more often than sugar gliders in captivity. The use of torpor is most frequent during winter, likely in response to low ambient temperature, rainfall, and seasonal fluctuation in food sources.

Sugar gliders are seasonally adaptive omnivores with a wide variety of foods in their diet, and mainly forage in the lower layers of the forest canopy. Sugar gliders may obtain up to half their daily water intake through drinking rainwater, with the remainder obtained through water held in its food.[30] In summer they are primarily insectivorous, and in the winter when insects (and other arthropods) are scarce, they are mostly exudativorous (feeding on acacia gum, eucalyptus sap, manna,[b] honeydew or lerp). Sugar gliders have an enlarged caecum to assist in digestion of complex carbohydrates obtained from gum and sap.

To obtain sap or gum from plants, sugar gliders will strip the bark off trees or open bore holes with their teeth to access stored liquid. Little time is spent foraging for insects, as it is an energetically expensive process, and sugar gliders will wait until insects fly into their habitat, or stop to feed on flowers. Gliders consume approximately 11 g of dry food matter per day. This equates to roughly 8% and 9.5% of body weight for males and females, respectively.

They are opportunistic feeders and can be carnivorous, preying mostly on lizards and small birds. They eat many other foods when available, such as nectar, acacia seeds, bird eggs, pollen, fungi and native fruits.[43][44] Pollen can make up a large portion of their diet, therefore sugar gliders are likely to be important pollinators of Banksia species.

Reproduction

Like most marsupials, female sugar gliders have two ovaries and two uteri; they are polyestrous, meaning they can go into heat several times a year. The female has a marsupium (pouch) in the middle of her abdomen to carry offspring. The pouch opens anteriorly, and two lateral pockets extend posteriorly when young are present. Four nipples are usually present in the pouch, although reports of individuals with two nipples have been recorded. Male sugar gliders have two pairs of bulbourethral glands[46] and a bifurcated penis to correspond with the two uteri of females.

The age of sexual maturity in sugar gliders varies slightly between the males and females. Males reach maturity at 4 to 12 months of age, while females require from 8 to 12 months. In the wild, sugar gliders breed once or twice a year depending on the climate and habitat conditions, while they can breed multiple times a year in captivity as a result of consistent living conditions and proper diet.

A sugar glider female gives birth to one (19%) or two (81%) babies (joeys) per litter. The gestation period is 15 to 17 days, after which the tiny joey 0.2 g (0.0071 oz) will crawl into a mother's pouch for further development. They are born largely undeveloped and furless, with only the sense of smell being developed. The mother has a scent gland in the external marsupium to attract the sightless joeys from the uterus. Joeys have a continuous arch of cartilage in their shoulder girdle which disappears soon after birth; this supports the forelimbs, assisting the climb into the pouch. Young are completely contained in the pouch for 60 days after birth, wherein mammae provide nourishment during the remainder of development. Eyes first open around 80 days after birth, and young will leave the nest around 110 days after birth. By the time young are weaned, the thermoregulatory system is developed, and in conjunction with a large body size and thicker fur, they are able to regulate their own body temperature.

Note the patagium (wing flap) on this individual feeding on honey at Chambers in the Atherton Tablelands

Breeding is seasonal in southeast Australia, with young only born in winter and spring (June to November). Unlike animals that move along the ground, the sugar glider and other gliding species produce fewer, but heavier, offspring per litter. This allows female sugar gliders to retain the ability to glide when pregnant.

Socialisation

Sugar gliders are highly social animals. They live in family groups or colonies consisting of up to seven adults, plus the current season's young. Up to four age classes may exist within each group, although some sugar gliders are solitary, not belonging to a group.They engage in social grooming, which in addition to improving hygiene and health, helps bond the colony and establish group identity.

Within social communities, there are two codominant males who suppress subordinate males, but show no aggression towards each other. These co-dominant pairs are more related to each other than to subordinates within the group; and share food, nests, mates, and responsibility for scent marking of community members and territories.

Territory and members of the group are marked with saliva and a scent produced by separate glands on the forehead and chest of male gliders. Intruders who lack the appropriate scent marking are expelled violently. Rank is established through scent marking; and fighting does not occur within groups, but does occur when communities come into contact with each other. Within the colony, no fighting typically takes place beyond threatening behaviour. Each colony defends a territory of about 1 hectare (2.5 acres) where eucalyptus trees provide a staple food source.

Sugar gliders are one of the few species of mammals that exhibit male parental care. The oldest codominant male in a social community shows a high level of parental care, as he is the probable father of any offspring due to his social status. This paternal care evolved in sugar gliders as young are more likely to survive when parental investment is provided by both parents. In the sugar glider, biparental care allows one adult to huddle with the young and prevent hypothermia while the other parent is out foraging, as young sugar gliders aren't able to thermoregulate until they are 100 days old (3.5 months).

There are no distribution maps for Krefft’s currently and the taxon is not universally accepted. I do believe the read part of this map will be the primary distribution area however.

Krefft's glider (Petaurus notatus) is a species of arboreal nocturnal gliding possum, a type of small marsupial. It is native to most of eastern mainland Australia and has been introduced to Tasmania. Populations of Petaurus from New Guinea and Indonesia previously classified under P. breviceps are also tentatively classified under P. notatus by the American Society of Mammalogists, but likely represent a complex of distinct species. As most captive gliders referred to as "sugar gliders" in at least the United States are thought to originate from West Papua, this likely makes them Krefft's gliders, at least tentatively.

Taxonomy

It is closely allied with the sugar glider (P. breviceps), with which it was long taxonomically confused. A 2020 study partially clarified the taxonomy of the sugar glider and split it into three species: the savanna glider (P. ariel), the sugar glider (P. breviceps sensu stricto) and Krefft's glider (P. notatus). The large range throughout eastern Australia once attributed to the sugar glider is now thought to actually be that of Krefft's glider; under the new taxonomy, the sugar glider has a smaller range in the coastal forests of Queensland and New South Wales.

Description

The species can be distinguished from P. breviceps by its more clearly defined mid-dorsal stripe and a more attenuated tail, with longer fur at the base which shortens towards the tip. P. notatus also has a white tip to its tail.

Distribution

It is widely distributed throughout eastern Australia, and may be the most widespread of all Australian Petaurus species. It ranges from coastal northern Queensland (albeit not the Cape York Peninsula, which is thought to be occupied by an unknown Petaurus species that may represent P. gracilis or another species) throughout most of inland Queensland and New South Wales south to Victoria and the southeastern corner of South Australia. In southern Queensland and most of New South Wales, the Great Dividing Range serves as a barrier from the coastal areas which are occupied by the sugar glider, although their ranges may overlap in some places. The species is also sympatric with the mahogany glider and yellow-bellied glider in parts of its range. The earliest Krefft's glider (originally identified as sugar glider) fossils were found in a cave in Victoria and are dated to 15,000 years ago, at the time of the Pleistocene epoch.

Populations of Petaurus in New Guinea likely represent a distinct species complex, but have been tentatively classified within P. notatus until they can be further studied. These gliders are also found in the Bismarck Archipelago, Louisiade Archipelago, and certain isles of Indonesia, Halmahera Islands of the North Moluccas.

Introduction to Tasmania

According to naturalist Ronald Campbell Gunn, no Petaurus species is indigenous to Tasmania. He concluded that Krefft's glider (then thought to have been sugar gliders) had been brought to Launceston, Tasmania as pets from Port Phillip, Australia (now Melbourne), soon after the founding of the port in 1834. Some Krefft's gliders had escaped and quickly became established in the area. The facilitated introduction of the sugar glider to Tasmania in 1835 is supported by the absence of skeletal remains in subfossil bone deposits and the lack of an Aboriginal Tasmanian name for the animal.

Krefft’s Glider seen in the Eucalyptus forests of Lammington NP can be easily identified based on the prominent white tail tip.

The species has been identified as a threat to the survival of the swift parrot, which breeds only in Tasmania. Reduction in mature forest cover has left swift parrot nests highly vulnerable to predation by Krefft's gliders, and it is estimated that the parrot could be extinct by 2031.[

They have a broad habitat niche, inhabiting rainforests and coconut plantations in New Guinea; and rainforests, wet or dry sclerophyll forest and acacia scrub in Australia; preferring habitats with Eucalypt and Acacia species. The main structural habitat requirements are a large number of stems within the canopy, and dense mid and upper canopy cover, likely to enable efficient movement through the canopy.

It has been suggested that the expanding overseas trade in Petaurus was initiated from illegally sourced sugar gliders from Australia, which were bred for resale in Indonesia. DNA analysis, however, indicates that "the USA (sugar) glider population originates from West Papua, Indonesia with no illegal harvesting from other native areas such as Papua New Guinea or Australia". Furthermore, this study (which preceded the break-up of P. breviceps into P. notatus, P. ariel and P. breviceps) indicated that West Papuan Petaurus gliders and their US pet trade derivatives belong to a sister group to the Australian Petaurus gliders.

There have been media and internet articles which evidence a history of cruelty, and reporting on why Krefft's gliders should not be kept as pets. There are glider rescue organisations that cope with surrendered and abandoned Krefft's gliders.

Krefft's gliders are popular as pets in the United States, where they are bred in large numbers. Most states and cities allow Krefft's gliders as pets, but they are prohibited in California, Hawaii, Alaska, and New York City.[26] In 2014, Massachusetts changed its law, allowing Krefft's gliders to be kept as pets. Some other states require permits or licensing. Breeders of Krefft's gliders are regulated and licensed by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) through the Animal Welfare Act.

Krefft's Glider (Petaurus notatus) Oreilly's at Lamington NP, Queensland